Creating a more favourable enabling ecosystem for the mental wellbeing of children and young people.

The weaving of resilient communities-in-place is hampered by the dis-incentivising of preventative behaviours by self-contained public service models structured and resourced in a way that only permits them to act in moments of crisis.

For Cultures of Resilience, UAL May 2016

In late 2014, Norfolk & Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust (NSFT), together with users of its youth mental health service, embarked on a process of creative and critical appraisal conceived by Early Lab.

Twelve months in, the pull of the specific context in rural Norfolk broadened the original scope of the project. The experiment began with the aim of sketching out new visions of a youth mental health service, but the urgent need for the system to function preventatively has necessitated attention in areas outside of the service itself. That is, scrutiny of the socio-ecological conditions in the region that a youth mental health service would anticipate.

Analysis

Questions are being asked of the life experiences of children and young people that contribute to them needing or not needing the support of a mental health service.1 These questions concern the most important relationships children have; with parents, carers, siblings, peers, teachers, neighbours and neighbourhoods. Children can strengthen these ties by better communication of their thoughts and feelings. Understanding the process through which they can be helped to achieve this is a primary aim of the project and one that renders any immediate review of child contact with health services, social services or youth justice officials as premature.

Complexity demands integration

A focus on the nature of human relationships will confirm that a child’s mental health, (that their social experiences contribute to significantly), can’t be managed or even fully understood through the lens of a single public service sector.2 Yet this is what is currently expected of the NHS – for the health model to be primarily responsible when the mental health of a child subsides. And this is even though the contributory factors are highly likely in many children to have been triggered, aggravated or even caused by events outside the biological realm of health. Obviously, circumstances at home or in school, for example, contribute fundamentally to the wellbeing of children. Traditionally however, these domains are the separate sanction of local authority social services or education bodies, should wellbeing be seriously threatened.

Plainly, lives as they are lived are far more complicated and mean that the real life concerns of each public service body are mutual: intricately intertwined despite the Government mandates that tend to erect barriers between them. Over the years, discrete public service sector cultures combined with contradictory operating incentives have bred, and this has made the cross-agency collaboration that is so essential for youth mental health very challenging. Without the early warning signals that cross-agency integrated care would provide, the NHS youth mental health service is reduced to crisis-response mode: only able to act when it is already too late. Its own ideals of prevention and early intervention pushed further out of reach.

The weaving of resilient communities-in-place is hampered by the dis-incentivising of preventative behaviours by self-contained public service models structured and resourced in a way that only permits them to act in moments of crisis.3 In the particular case of youth mental health, if the sirens are blaring then one can be sure irreversible damage has already been done and unavoidably a huge cost already incurred. The metaphor of ‘the safety-net’ fails in youth mental health – it is reactive when what is required is proactivity – and this is a false economy. A whole healthcare system predicated on only acting when you fall, when in fact as far as the wellbeing of young people and children is concerned the ‘safety-net’, in these days of austerity at least, is lying on the ground.

Vision

The kind of community that this project aims to produce is one in which the issue of mental health is promoted and therefore highly visible.4 A community that is:

Rooted – one empowered by access to emotional tools that help to build in its children and young people the capacity to cope with the inevitable ups and downs of life. A kind of active coping that is co-produced through informal interaction with their peers and families in a community fortified with high relational intensity and strong social ties.

Open – but also a community in which mental ill-health awareness has reduced the stigma associated with it to a level that permits formal support for it to be explicitly promoted by its institutions (education, health, social, justice) that can introduce lighter forms of involvement through a range of social tie strengths and relational intensities.5 This would allow a public service consisting of cross-agency integrated care to be clearly visible and easily accessible very early: as soon as the first emergent behaviours, before any crisis is yet apparent – preventatively.

In this scenario, NSFT is a top-down public service organisation that, driven by a desire to be preventative, is blurring its boundaries with other public service domains and enthusiastically adopting forms of bottom-up and peer-to-peer interaction. It is becoming hybrid: a form of collaborative social enterprise with grassroots tendencies that binds it to its communities. It takes a long-term view, is focussed on the wellbeing of its territory6 while being connected to global flows of information.7 Its clusters of projects aim at contributing to a planning framework8 for its territory and it innovates on an ongoing and open-ended9 basis.

Proposals

- Use existing social organisation – home, school, community – as element of the mental health ecosystem10

In response with Early Lab, NSFT and its complimentary public sector colleagues are thinking holistically: what are the ways to reduce the incidence of young people ‘falling’? Can this be achieved by creating a more favourable enabling ecosystem11 (home, school, community) in which young people prefer preventative behaviours that make it easier for them to remain ‘standing’ without recourse to the formal interventions of a mental health service?

- Schools – the role of places as enablers

Early Lab and NSFT see primary and secondary schools as the key sites in which to rekindle the favourable conditions (that could help make the reduction of the incidence of young people ‘falling’ possible) because they are hubs of community.12

- Balance different kinds of social encounter in terms of degree of involvement and quality of interaction13

Built over years, schools share the strong social ties with children that families, friends and communities do, but balance the informal encounters of high relational intensity that children experience outside of school in their community, with a formal low relational intensity in school.

- Wellbeing champion – the role of social people as connectors14

To make genuine early-intervention possible, Early Lab and NSFT plan to introduce into schools a champion for mental wellbeing. This is a teacher-trained wellbeing champion with a good grasp of mental healthcare principles, shared by three schools in a region. The wellbeing champion would be in a pivotal position to identify early any signs of concern just as they begin to surface, and with powers of referral, help prevent mild difficulties becoming acute. Their alternating part-time presence maintaining weak social ties with the three schools would loosen up tightknit social fabrics dominated by strong social ties. Added to that, their close contact with sectors outside of education such as health, social care and youth justice, would open up schools and their communities-in-place to the wider enabling ecosystem of the territory in which they are situated.

The role of the design process

Early Lab has found its project partners, that’s youth mental health provider NSFT, the head of Norfolk County Council Children’s Services, the head of its Clinical Commissioning Group, as well as representatives of the local voluntary sector, to be very keen to find ways to work together despite their cultural and operational contrasts. This kind of diversity is however not a problem: a range of approaches is in fact essential when it comes to effecting good collaboration and designers, (designers for social innovation, at least), know this well.

Creating the conditions for a social conversation

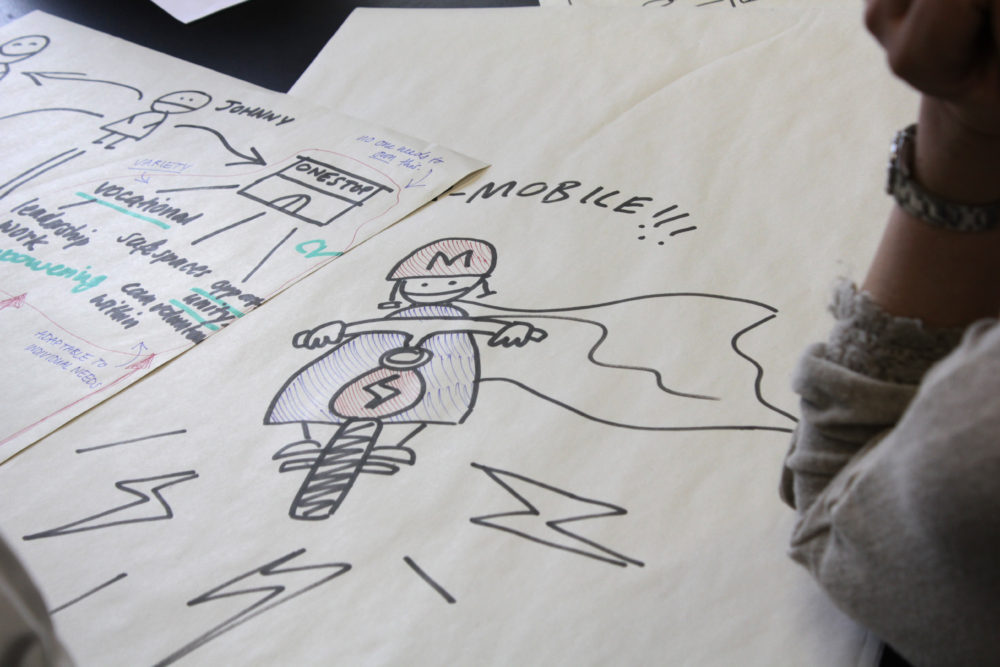

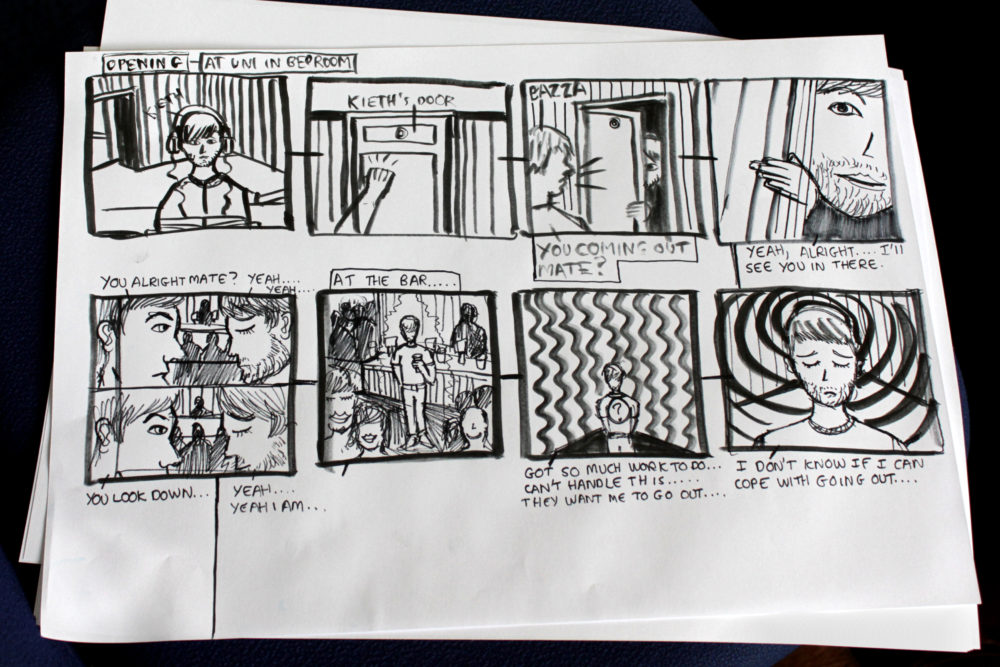

Through Early Lab’s making-workshops, design has won a significant role for itself in being an alternative language all participant entities can try out when dreaming up new approaches to youth mental health. Here, with health and social care professionals, thinking-through-making15 provides them with a model-agnostic process for stakeholder engagement and concept co-development, circumventing the barriers hoisted by siloed public service sector-thinking, and ensuring cross-agency collaboration is more effective.

The lesson from Early Lab’s making-workshops is design can operate in this way because it is alien enough as a language and mode of thought for all public sector participants to act as a leveller for them. The shared unfamiliarity can create a positive apprehension that while not removing discrepancies between parties, can overshadow them16 and enable a group that remains diverse in perspective to be co-actors in an equitable process.17

Creating conversation tools to empower the conversation

A process of co-design with making at its core transcends what would traditionally be mere verbal discussion because communication takes place through vibrant physical and visual objects made in the workshop.18 Meaningful objects, that not only unlock local capacities, capture knowledge and tell stories, they also provide a different kind of reflection, a novel feedback that participants experience viscerally. When made visual and physical, new ideas and scenarios can appear more tangible, real, actionable.19 NSFT’s verdict on the Early Lab process was that a route to service transformation now appeared more achievable and in large part because they could see it laid out and animated in front of them.

References

- ^The Department for Education, UK Government with Department of Health’s online mental health training team; MindEd; NHS England and the Children and Young People’s Improving Psychological Therapies programme team (CYP&IAPT); Professor Mick Cooper, Professor Peter Fonagy; SEN at DoE; DoE’s Primary and Secondary Heads’ Reference Groups (2015), Mental health and behavior in schools: departmental advice for school staff. Reference: DFE-00435-2014. Download at http://www.gov.uk/government/publications

- ^“…Services need to be outcomes-focused, simple and easy to access, based on best evidence, and built around the needs of children, young people and their families rather than defined in terms of organizational boundaries. Delivering this means making some real changes across the whole system. It means the NHS, public health, local authorities, social care, schools and youth justice working together to: place the emphasis on building resilience, promoting good mental health, prevention and early intervention. Simplify structures and improve access: by dismantling artificial barriers between services by making sure that those bodies that plan and pay for services work together… Deliver a joined up approach: linking services so care pathways are easier to navigate for all children and young people, including those who are most vulnerable, so people do not fall between gaps.” Children and Young People’s Mental Health and Wellbeing Taskforce (March 2015): Future in mind: promoting, protecting and improving our children and young people’s mental health and wellbeing. Some Taskforce members include: Sarah Brennan, Chief Executive, Young Minds; Prof Mick Cooper, Prof of Counselling Psychology, University of Roehampton; Margaret Cudmore, Vice Chair, Independent Mental Health Service Alliance; Prof Peter Fonagy, National Clinical Lead CYP&IAPT, NHS England, & Chief Executive, Anna Freud Centre; Anne Spence, Taskforce Policy Lead; Dr Jon Wilson, Clinical Lead, Norfolk Youth Service, NSFT. NHS England, Department of Health, UK Government. Ref. No 02939. Published to gov.uk, in pdf format only. http://www.gov.uk/dh

- ^“…sometimes the health service has been prone to operating a ‘factory’ model of care and repair, with limited engagement with the wider community, a short-sighted approach to partnerships, and underdeveloped advocacy and action on the broader influencers of health and wellbeing. As a result we have not fully harnessed the renewable energy represented by patients and communities, or the potential positive health impacts of employers and national and local governments.” NHS England with Care Quality Commission, NHS Health Education England; Monitor; Public Health England; Trust Development Authority (October 2014). NHS Five Year Forward View. Chapter 2, What will the future look like? A new relationship with patients and communities, pdf page 10.

- ^The vision of a community that is both rooted and open is one of the outcomes from Early Lab Workshops A & B conducted with lead clinicians of the youth mental health service of Norfolk & Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust (NSFT). These workshops were conceived and conducted by Early Lab during its Project 1 field trip to Norfolk in late March/early April 2015.

- ^The concept of ‘social tie strengths’ and ‘relational intensities’ comes from Ezio Manzini (2015). Design, When Everybody Designs: an introduction to Design for Social Innovation: The MIT Press: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA. 2015. ISBN 978-0-262-02860-8. Pages 101-104.

- ^Ibid., page 193. Use of the word ‘territory’ in this context is borrowed from the Italian Territorialist School via Ezio Manzini.

- ^Ibid., page 25. The idea of being local yet exposed to global flows of information comes from Ezio Manzini’s concept of ‘cosmopolitan localism’.

- ^Ibid., page 187. “The framework project is a design and communications initiative including scenarios (to give local projects a common direction), strategies (to indicate how to implement scenarios), and specific supporting activities (to systemize the local projects, to empower them, and to communicate the overall project)” – Ezio Manzini.

- ^Ibid., page 68. “In today’s turbulent environment, organisations evolve over time, calling for a constant upgrading of their way of working.” – Ezio Manzini.

- ^This proposal is one of the outcomes from Workshops A & B conducted with lead clinicians of the youth mental health service of Norfolk & Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust (NSFT). These workshops were conceived and conducted by Early Lab during its Project 1 field trip to Norfolk in late March/early April 2015.

- ^The use of the term ‘favourable enabling ecosystem’ comes from Ezio Manzini. “Collaborative organisations are living organisms that require a favourable environment to start, last, evolve into mature solutions, and spread.” – Ezio Manzini (2015). Design, When Everybody Designs: an introduction to Design for Social Innovation: The MIT Press: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA. 2015. ISBN 978-0-262-02860-8. Page 90.

- ^This proposal is one of the outcomes from Workshops A & B conducted with lead clinicians of the youth mental health service of Norfolk & Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust (NSFT). These workshops were conceived and conducted by Early Lab during its Project 1 field trip to Norfolk in late March/early April 2015.

- ^The language for the framing of this proposal benefits from Ezio Manzini’s emphasis on the importance of the social role of weak social ties: “…it is precisely these weak ties that make the social system more open and able to communicate. Indeed… in the words of Granovetter, when strong ties predominate ‘information is self-contained and experiences are not exchanged.’ This means… that organisations tend to close in on themselves, not exchange experiences, and fail to evolve.” – Ezio Manzini (2015) Design, When Everybody Designs: an introduction to Design for Social Innovation: The MIT Press: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA. 2015. ISBN 978-0-262-02860-8. Page 102. Mark Granovetter (1973), The Strength of Weak Ties, American Journal of Sociology 78, no. 6, p.1360-1380.

- ^This proposal is one of the outcomes from Workshops A & B conducted with lead clinicians of the youth mental health service of Norfolk & Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust (NSFT). These workshops were conceived and conducted by Early Lab during its Project 1 field trip to Norfolk in late March/early April 2015.

- ^Early Lab use of thinking-through-making has drawn extensively on the public engagement experiences of designer and UAL tutor at Camberwell College of Arts, Fabiane Lee-Perrella, through her practice Flour. http://www.ourflour.com/flour/about/

- ^“As a participant [of the Early Lab field trip workshops] it was lovely to witness a level of cohesion between different services (that I had never witnessed before), all willing to let their ‘creative juices’ flow in a fun environment for a common cause: improving the mental health service experience and access for local young people.” Tim Clarke (2015), Research Clinical Psychologist, NSFT reflecting on his experience of the Early Lab Project 1 field trip of March/April 2015 on the NSFT blog What’s The Deal With… http://www.whatsthedealwith.co.uk/blog/%E2%80%98 creative-meeting-minds%E2%80%99 Accessed on 22 June 2016.

- ^Early Lab views all participants in a co-design workshop as ‘co-actors in an equitable process’ as opposed to a traditional ‘design-thinking’ method that has a propensity to present the designer as a facilitator and to present the participant as a person who is merely engaged instead of being seen as an individual acting off their own back, their own agency. The Early Lab approach (mindful of the dangers of paternalism) continues Fabiane Lee-Perrella’s practice at Flour that staunchly opposes the designer acting as background facilitator in these communal thinking-through-making processes. The naming of the ‘fraternalistic’ approach: ‘co-actors in an equitable process’ comes from Adam Thorpe and Lorraine Gamman whose writing, research and advice inspires us greatly – particularly this text: Design uwith/u Society: why socially uresponsive/u design is good enough; Adam Thorpe and Lorraine Gamman (2011); CoDesign Journal 7:3-4, Sept-Dec 2011, 217-230. Taylor & Francis: ISSN 1745-3755 online. p.222. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/ 15710882.2011.630477 Accessed on 22 June 2016.

- ^“I argue no more and no less than that the capacities our bodies have to shape physical things are the same capacities we draw on in social relations.” “A more accurate if rather more complex process of visualization is required particularly at the edge, the zone in which people have to deal with difficulty; we need to visualize what is difficult in order to address it.” – Richard Sennett (2008). Richard Sennett, The Craftsman: Penguin Books, London, 2008. ISBN: 978-0-141-02209-3. p. 290 and 230.

- ^“Methods and tools for making give people – designers and non-designers – the ability to make ‘things’ that describe future objects, concerns or opportunities. They can also provide views on future experiences and future ways of living.” Elizabeth B. -N. Sanders & Pieter Jan Stappers (2014): Probes, toolkits and prototypes: three approaches to making in codesigning. CoDesign Journal 10:1, 5-14, 6. DOI: 10.1080/15710882.2014.888183. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/ 15710882.2014.888183