Transition Design: powered by ordinary human beings from all walks of life

Amid the dust and rubble of one-size-fits-all ideologies, experimentation with models of self-governance is thriving. These are the conditions enabling a new design paradigm within which ‘transition design’ is growing. Borrowing from ecology and the social sciences, transition designers are beginning to understand highly complex systems attendant with current global challenges. In on-the-ground alliances with all other practices, they are learning how to leverage the sensitive dynamics of systems for social and environmental benefit.

This text is an edited version of one written to introduce a presentation of Early Lab at NUA (Norwich University of the Arts), Norwich, 23 March 2017.

Summary

Amid the dust and rubble of one-size-fits-all ideologies, experimentation with models of self-governance is thriving. These are the conditions enabling a new design paradigm within which ‘transition design’ is growing. Borrowing from ecology and the social sciences, transition designers are beginning to understand highly complex systems attendant with current global challenges. In on-the-ground alliances with all other practices, they are learning how to leverage the sensitive dynamics of systems for social and environmental benefit.

Emerging is a new worldview propelled by inclusive investment in the diverse and abundant competences of everyone: our practices, agency and collaborative capacity in the places and communities where we all live and work. It’s a new mindset that has great potential as a platform for self-governance building sustainable policy expertise and resilience through repeating cycles of feedback and response, iterating continuously.

Governments in the developed world are at a loss for how to respond effectively to the current global challenges of climate change, migration, terrorism and inequality. While there are many reasons for this, a contributory factor is that its leaders are limited by an outmoded worldview that places faith exclusively in elites – people like them – to provide solutions. To continually produce an elite, institutions have to be configured to legitimate a system of privilege and neglect: for a tiny minority and vast majority respectively.

Government and the relentless erosion of self-motivation

The institutions of power have grossly underestimated the scale and multi-layered complexity of the systems concomitant with global challenges (climate change, migration, terrorism, inequality, depleting biodiversity). Leaders have believed they could predict the future, change the world and solve the big problems. Apart from the deluded, they are now realizing that they can’t and never will. Their consolation is the frightening ease with which they can protect their own vested interests, perpetuating their worldview despite its zombie state.

In the description to HyperNormalisation1, the film by British filmmaker Adam Curtis, it says: “We live in a time of great uncertainty and confusion. Events keep happening that seem inexplicable and out of control. Donald Trump, Brexit, the war in Syria, the endless migrant crisis, random bomb attacks. And those who are supposed to be in power are paralysed – they have no idea what to do.”

Belgian political theorist Chantal Mouffe blames this crisis on the complacency of politicians who thought it was possible to have a cosy “consensus of the middle”: centre left with centre right. Therefore, “within the field of traditional democratic parties” there has been “no possibility of fighting for an alternative”. Any alternative to neoliberal capitalist economics, that is. This “created the terrain for the success of those right-wing populist parties. Because they are the ones who say: ‘No, no! There is an alternative – we are going to give back to the people the possibility to decide.’”2

The people, are members of a large skills community that for the last thirty years or so multiple Western governments have placed no value in – one that seems “to have disappeared from the public eye”3. Their susceptibility to campaign slogans promising to “take back control” and “make America great again” should not have been the surprise it was given the absence of any genuinely alternative vision that might have included them. So, as can be seen, the people are lashing out as soon as the opportunity presents itself.

The governing consensus of the middle is not only remote and self-serving but also, it turns out, owned by the corporate lobbying superrich. Racist populism is currently the only opposition to this: a ‘nationalism’ intent on extended relaxation of financial and corporate controls (that will weaken public health protections) funded by vested interests campaigning that climate change is an international conspiracy. Understandable then that the people, (at least those of whom that want to see change likely to secure human beings a sustainable future on this planet), should want to start recovering their own innate capacities for governance.

The sociologist Richard Sennett writes that “learning to do good work” collectively, together, makes “human beings more capable of self-governance.” There is “no lack of intelligence among ordinary human beings” to make that possible. Its unfortunate then that the way the developed world is run has created a society that Sennett says threatens “the drive to do good work.” 4

Capitalism (that’s neo-liberalised industry, services, technology, media) has been de-skilling us of the ability to self-govern for decades. For Sennett, the tiny minority establishments, the elites, are contriving to persuade everyone else, into believing that they are not up to the job. He sees this as an attack on the emotions, designed to destroy motivation. Interestingly, Sennett claims “motivation is a more important issue than talent in consummating craftsmanship”.5 Designers can replace the word craftsmanship here with design or social innovation if they like.

Actually, “the capacity to work well”, Sennett estimates, “is shared fairly equally among human beings”.6 Its just that those in power organise education narrowly, so that for most people, it doesn’t test them on what they are good at – only on what they aren’t. The measurement of intellectual capacity is rigged. Rigged to give licence to those who want to remain in power, rigged to give them a licence to neglect everyone else by diverting resources elsewhere – to the lucky few, whose arbitrary talents happen to coincide with what is measured assuming they do what they are told and can afford to play the system.

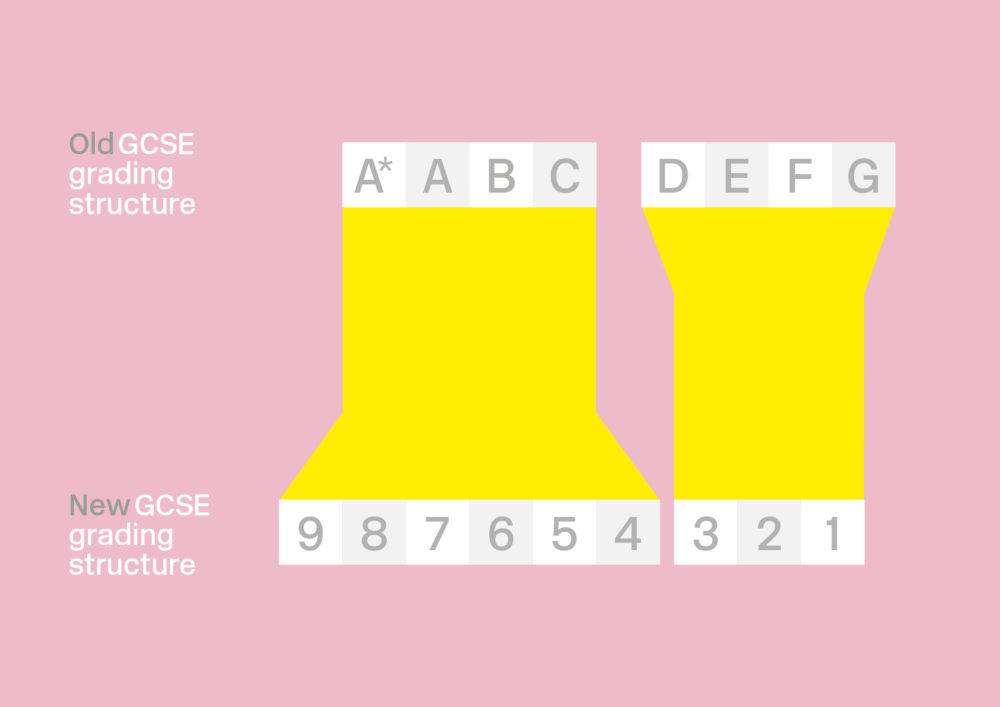

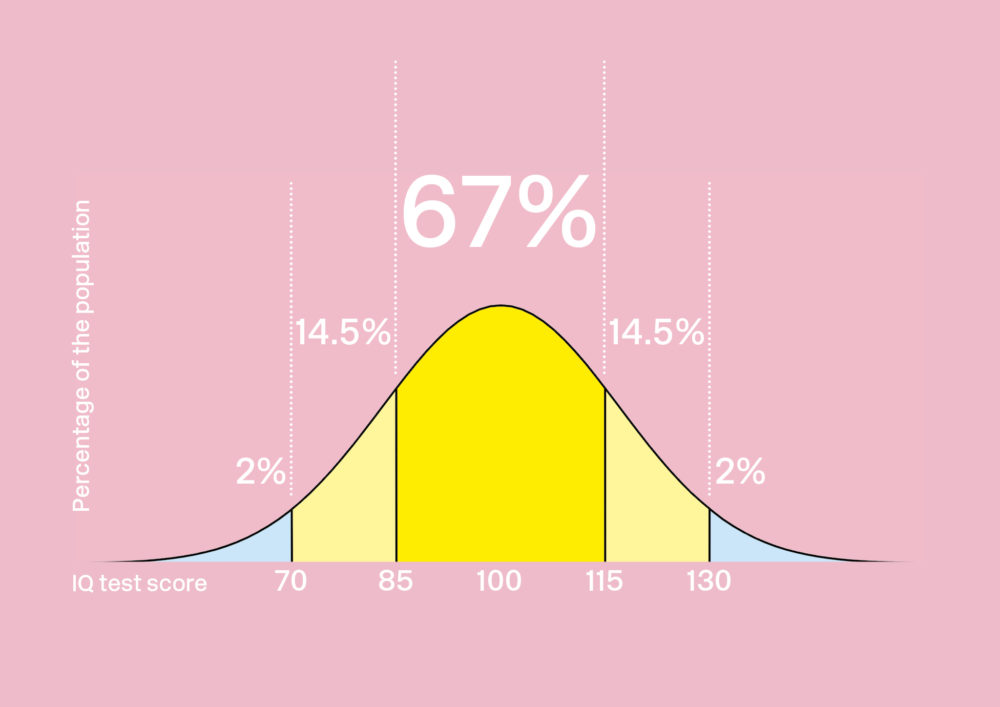

Below are two graphic examples of metrics that are used to normalise those corrupt permissions: the new GCSE grading structure (my example), and the notorious IQ test (Sennett’s example).

From 2017 the UK government’s Department for Education (DfE) is beginning the phasing out of lettered grades (A*-G) in favour of numbered grades (9-1). Notable is the inflation of the higher grades and the compression of the lower grades. The differences between the four higher grades A*-C have been magnified to extend to six grades numbering 9-4. While the distinctions between the four lower grades D-G have been collapsed to three grades, 3-1.

According to the DfE’s own statistics7, roughly 33% of children will be expected to attain or fail to attain grades 3-1 in 2017, while only 20% of children will manage to attain grades 9-7. One questions the purpose of investing in greater differentiation at the top end of the scale when it clearly benefits a smaller proportion of the year’s students. It makes more sense to signal variations of exam performance at the bottom end of the scale because here it serves a greater number of students. At the bottom end, students are not performing at their full capacity and in need of further educational investment at an appropriate level and in subjects that suitably adjusted metrics could help provide guidance on. The DfE’s adjustment of the grading system exposes a bias in preference of those students already doing very well to the potential detriment of students in need of more support.

In his book The Craftsman from 2008, Richard Sennett writes “the person with the IQ score of 100 is not much different in ability to the person with a score of 115, but the 115 is much more likely to attract notice… the shape of the bell curve raises a question about the middle” – that’s the big hump where the majority of people are. Quite simply he asks, “why the blind spot to its potential?” Sennett’s judgement of the IQ test, that is equally applicable to the new GCSE numbering, is damning:

“Inflating small differences in degree into large differences in kind legitimates the system of privilege. Correspondingly, equating the median with the mediocre legitimates neglect”.

Sennett concludes that this is “one reason why Britain directs proportionately more resources into elite education than into technical colleges and why in America it proves so hard to find charitable contributions to vocational schools.”8

Self-governance and drawing on the competences of everyone

Ok, so you have been labelled a failure: dismissed as one of a mass of also-rans who will never come to anything; had your confidence crushed and your sense of wellbeing diminished irreparably. Welcome to the club. So what possible use can there be for us in this talk of self-governance? Aren’t we getting ideas above our station?

Richard Sennett’s response to raise us out of our dejected torpor would be to draw our attention to “the capacities we draw on in social relations” that he says are the same capacities “our bodies have to shape physical things”9. This observation underpins his faith in democracy, a faith he shares with the movement of pragmatism10. Sennett says “the capacities on which human beings draw to develop skills…” (skills to shape physical things and hence social relations) “…are widely diffused among human beings rather than restricted to an elite”11 despite what our public and private institutions would have us believe.

No one reads your blog posts, likes your photos and trolls have humiliated you on social media. Give it up! Your “obsessive need incessantly to express and share”12 reduces you to a fractal: “an interchangeable producer of micro-fragments of recombinant semiosis”13 – fodder for the bulging internet monopolies.

In waking us up to our own intrinsic capacities to self-rule, Sennett points to pragmatism’s insistence that “the remedy to these ills…” (that’s the atomisation and alienation of digital mass media) “…must lie in the experience, on the ground, of citizen participation, participation that stresses the virtues of practice…” (meaning practice over and above the solely theoretical, the merely academic) “…the virtues of practice with its repetitions and slow revisions”14. “Repetitions and slow revisions” sounds like the practice of co-design with its repeating prototyping cycles of iteration, testing, feedback and revision.

For me, the current political crisis is the pain of the shedding of one worldview and the trying on for size of a new radically different worldview. Sennett says proponents of the old, shrivelling worldview think that the failure of democracy is that it “demands too much of ordinary human beings” whereas Sennett himself thinks the old worldview is in crisis purely because modern democracy demands too little of us.

For Sennett, the institutions and tools of communication that will form the platform for a new worldview will need to “draw on and develop the competences that most people can evince in work”15. Or show in play for that matter, or art, design. “Work, which remains permeated with the play attitude, is art”16.

With all the global challenges that we currently have, you’d think that this is not a good time for this crisis of politics to be happening. But actually, the communication designer turned academic Terry Irwin17 points out that we have no choice. She reminds us of what Einstein said, that “problems cannot be solved within the same mindset that created them”, therefore “solutions to complex, interdependent problems confronting society in the 21st century must arise out of a new mindset or worldview upon which a new design paradigm can be based.” Irwin is emphatic: “the transition to a sustainable society is one of the biggest design challenges the human race has ever faced”. Meeting this challenge “will require countless designed solutions that will be created by people from all walks of life, using design thinking and design process.”18

That Irwin should specify “people from all walks of life”, I find significant. It turns out that all the ordinary human beings from all walks of life, despite our unremarkable GCSE grades and our irredeemably average IQ scores, are needed after all. The rest of the world needs us to believe, to have confidence in our own capacity to meet these challenges and reveal our so-far unmeasured abilities in our work – or play, as it might be. Irwin is in no doubt that “design affects and concerns everyone. Design is directly linked to the satisfaction of human needs… design is an ‘emergent’ property of humans striving to meet their needs. These needs can be as simple and mundane as planning an evening meal, or as large and consequential as the redesign of an urban transportation system or a course of treatment for a desperately ill patient. Society’s transition to a sustainable state is a challenge for a new breed of ‘transition designers’ working within a new design paradigm, across disciplinary and professional divides.”19

According to Paul Rodgers20, a Design Leadership Fellow of the AHRC (the UK’s Arts and Humanities Research Council), there is an enormous amount of design research going on in universities in the UK. This is good news for the discipline of design, but designers must not be complacent. Rodgers’ research also reveals that 75% of design research in the UK is happening within subjects other than design itself. Rodgers assures that, from what he can see, this 75% employs proper design methodologies and processes – that this is not simply a case of research teams opting to use the word design in the title in mere reflection of the current popular use of the word. Design is now a meta-discipline.

As early as the 1970s design researchers were, as Terry Irwin points out, already maintaining that “traditional linear, cause and effect design processes were inadequate for solving” the kind of complex ‘wicked problems’21 like climate change or global terrorism, now facing us. “Due to their multiple levels of complexity and stakeholders with opposing viewpoints or worldviews” these design researchers “argued that it is impossible to arrive at a complete or fully correct design solution”. This is because this kind of complex problem not only “continually mutates and evolves” but is dynamically comprised of a “dense web of relationships” to other problems “that any attempt to solve” will “ramify throughout in unpredictable ways”22.

Design that fully acknowledges the complexity and unpredictability of its conditions this way has pragmatic expectations of solutions. Not only will solutions always be incomplete and not fully correct, they will be short-lived. The aim of solutions can no longer be to achieve order (the involuntary compulsion of most designers inculcated by the traditional design process) since order equates to balance and equilibrium, which in systems that are alive means death. Instead, representing a huge challenge to managers clinging to certainty through impatiently planned workflows, design becomes more about programmes of on-the-ground engagement with diverse stakeholder groups. It becomes a sensing process of coping with ambiguity through experimentation with repeating, zigzagging cycles of iteration and feedback that first of all needs to help trans-disciplinary teams to simply learn to see – to “see the complexities and interdependent relationships that comprise a wicked problem”. This, Irwin says, “is a wicked problem in its own right”23.

In this agonistic space of interactions and interventions where designers attempt to anticipate the system perturbations they produce, dialogic relations succeed dialectic ones24. Design becomes less about the closure of problem-solving and more about problem-framing in its on-going support and maintenance of a succession of provisional positions being negotiated between interest groups. The earlier in the cycle of processes that designers join these negotiations the better. Early-stage design practice is less about the quick fix of curing symptoms, and instead, uses symptoms as clues to the health of a system. Clues that can inform the long-term strategy of a practice based on the pre-emptive: preventative action (as it is known in the health sector) to reduce the incidence of unhealthy symptoms appearing at all.

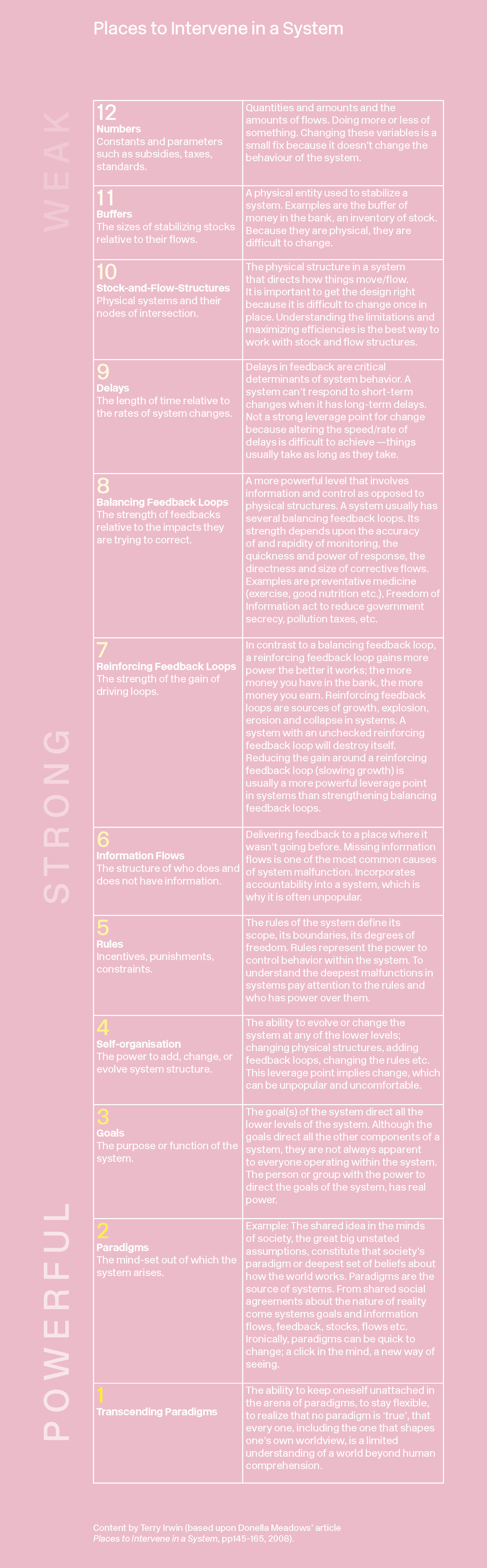

The recent work of early-stage design practice Early Lab25 (of which I’m co-founder), done with a regional NHS26 youth mental health service, is an example of co-design activity with preventative aims. Retreating from service design proposals specific to the youth mental health crisis in the health service itself, Early Lab is now focussing on aspects of the wider enabling system that can have an impact on wellbeing: education27. With hindsight, using the research of Donella Meadows28 it is possible to say that what Early Lab is doing together with leaders of the Norfolk & Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust, is identifying schools as the “leverage point” in the system – the point where it is felt “change can be created and directed” more powerfully29. Using Places to Intervene in a System (the table below), I can say that our interactions are likely to perturb the system in the following ways Meadows classifies: “8 – balancing feedback loops”, “7 – reinforcing feedback loops”, “6 – information flows”, “5 – rules”, “4 – self-organisation” and “3 – goals”. In these ways we are looking for leverage so that the culture of state primary and secondary schools can be transformed to improve the wellbeing of its students, staff, wider community-in-place and therefore reduce the strain on its local health service.

The Early Lab project30 is presented here as a small example of a form of self-governance. Together with service users and service providers, ordinary human beings (as Richard Sennett would see them), from all walks of life (as Terry Irwin would want), we envisioned what a new mental health system for children and young people in Norfolk and Suffolk would look like. This could not have been achieved if the project stakeholders – the NHS service users – didn’t think, didn’t believe they were up to it.

Early Lab links

The Early Lab approach.

Early Lab case study 1: re-envisioning services with a regional NHS mental health service.

This text is an edited version of one written to introduce a presentation of Early Lab work to design students and staff at NUA (Norwich University of the Arts), Norwich, 23 March 2017.

References

- ^ Adam Curtis, HyperNormalisation, October 2016 on BBC iPlayer: http://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/p04b183c/adam-curtis-hypernormalisation 31 March 2017

- ^ Chantal Mouffe in an interview with Patrick Delaney, March 2015. Issue 14: movement, Digital Development Debates: http://www.digital-development-debates.org/issue-14-movement--introduction--society-is-always-divided.html 31 March 2017.

- ^ Édouard Louis, author of The End of Eddy. (London: Harvill Secker, 2 February 2017): https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/mar/19/interview-edouard-louis-the-end-of-eddy-front-national-marine-le-pen-kim-willsher 3 April 2017

- ^ Richard Sennett, The Craftsman. (London: Penguin Books, 5 February 2009), 285.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ofqual, A guide to GCSE results, summer 2016. 25 August 2016. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/a-guide-to-gcse-results-summer-2016 5 April 2017.

- ^ Richard Sennett, The Craftsman. (London: Penguin Books, 5 February 2009), 285.

- ^ Richard Sennett, The Craftsman. (London: Penguin Books, 5 February 2009), 290.

- ^ Richard Sennett, The Craftsman. (London: Penguin Books, 5 February 2009), 286.

- ^ Richard Sennett, The Craftsman. (London: Penguin Books, 5 February 2009), 291.

- ^ Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi, Heroes: Mass Murder and Suicide (Brooklyn, NY: Verso, 3 February 2015), 211.

- ^ Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi, Heroes: Mass Murder and Suicide (Brooklyn, NY: Verso, 3 February 2015), 139.

- ^ Richard Sennett, The Craftsman. (London: Penguin Books, 5 February 2009), 291.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Richard Sennett, The Craftsman. (London: Penguin Books, 5 February 2009), 288.

- ^ Terry Irwin is the Head of the School of Design at Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA. Her research is in Transition Design, a new area of design study, practice and research that argues for societal transition toward more sustainable futures. http://design.cmu.edu/people/faculty/terry-irwin#profile-main 10 April 2017.

- ^ Terry Irwin, Wicked Problems and the Relationship Triad. In Grow Small, Think Beautiful: Ideas for a Sustainable World, ed. Stephan Harding. (Totnes, Devon: Schumacher College, 2011). https://www.academia.edu/4655794/Wicked_Problems_and_the _Relationship_Triad_from_Grow_Small_Think_Beautiful_Ideas_for _a_Sustainable_World_from_Schumacher_College_Stephan_ Harding_ed._2011 10 April 2017.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Professor Paul Rodgers is the new Arts & Humanities Research Council leadership Fellow for Design from January 2017 for 3 years. He is Professor of Design at Imagination, Lancaster University. http://www.ahrc.ac.uk/newsevents/news/new-priority-area-fellows/ 10 April 2017.

- ^ Horst Rittel (1930-1990) was a design theorist best known for coining the term wicked problem. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horst_Rittel 10 April 2017.

- ^ Terry Irwin, Wicked Problems and the Relationship Triad. In Grow Small, Think Beautiful: Ideas for a Sustainable World, ed. Stephan Harding. (Totnes, Devon: Schumacher College, 2011). https://www.academia.edu/4655794/Wicked_Problems_and_the _Relationship_Triad_from_Grow_Small_Think_Beautiful_Ideas_for _a_Sustainable_World_from_Schumacher_College_Stephan_ Harding_ed._2011 10 April 2017.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Dialogic. "Unlike a dialectic process, dialogics often do not lead to closure and remain unresolved. Compared to dialectics, a dialogic exchange can be less competitive, and more suitable for facilitating cooperation." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dialogic#Distinction_between_ dialogic_and_dialectic 10 April 2017.

- ^ Early Lab is an early-stage design practice founded by Nick Bell and Fabiane Lee-Perrella in 2014 at University of the Arts London (UAL). Early Lab supports social innovation through the capacities that get activated when people make things together. Early Lab are working with NHS researchers in the area of mental health for children and young people. http://earlylab.org/ 10 April 2017.

- ^ The National Health Service (NHS) is the name of the public health services of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Health_Service 10 April 2017.

- ^ Early Lab, pupil wellbeing in schools project: http://earlylab.org/projects/pupil-wellbeing-in-schools/the-role-of-schools-in-the-wellbeing-and-mental-health-of-children-and-young-people/ 10 April 2017.

- ^ Donella Meadows (1941-2001) was a pioneering American environmental scientist, teacher and writer. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Donella_Meadows 10 April 2017.

- ^ Terry Irwin, Wicked Problems and the Relationship Triad. In Grow Small, Think Beautiful: Ideas for a Sustainable World, ed. Stephan Harding. (Totnes, Devon: Schumacher College, 2011). https://www.academia.edu/4655794/Wicked_Problems_and_the _Relationship_Triad_from_Grow_Small_Think_Beautiful_Ideas_for _a_Sustainable_World_from_Schumacher_College_Stephan_ Harding_ed._2011 10 April 2017.

- ^ Early Lab, service visioning with the NHS – account of the project in seven detailed steps: http://earlylab.org/projects/service-visioning-with-the-nhs/ 10 April 2017.