Using making to escape a paralysis made of the verbal.

There is something about making things, compared to merely discussing things. Something about visualizing things compared to merely writing them down that gets people thinking in a different way. Making thoughts and ideas visible, making them physical, when done in the right way, can carry a certain kind of magic.

Making things

There is something about making things, compared to merely discussing things. Something about visualising things compared to merely writing them down that gets people thinking in a different way. Making thoughts and ideas visible, making them physical, when done in the right way, can carry a certain kind of magic. This we know, but a recent UAL Early Lab design collaboration with a local NHS youth mental health service up in Norfolk brought this home to me once again.

Norfolk & Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust (NSFT) is continually reappraising the effectiveness of its youth mental health service and discusses issues of fitness-for-purpose often. NSFT’s challenge to Early Lab was to provide the impetus to get the lengthy process of service transformation design rolling for them. More specifically, to help them figure out how to make genuine connection with young people, and question a system model that puts up barriers to the quick and easy access to services young people need. Put simply, our task was to turn what for them feels like ‘just a lot of talk’ into a concrete plan of action. And most importantly, ensure their service users and service providers were at the centre of this work – that they were its authors.

Responding to this challenge, Early Lab’s multi-disciplinary team of eight UAL students and its two co-founders (myself and Camberwell 3D Design tutor Fabiane Lee-Perrella) travelled to Norwich last Easter to host a week-long series of workshops with NSFT’s service users and providers.

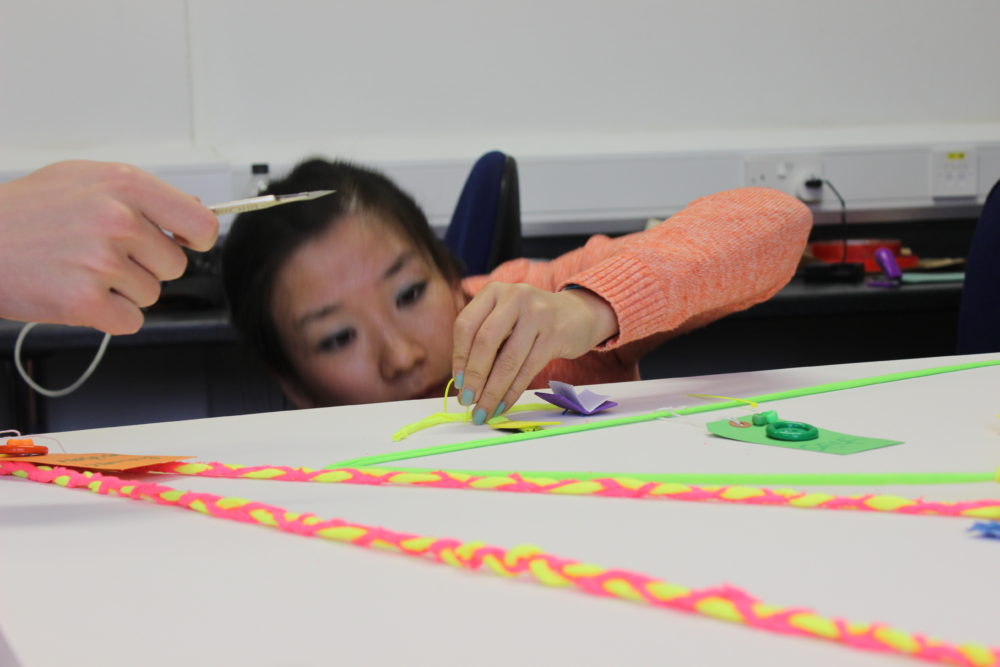

Six workshops, focused on 3 themes (people, places, stories), were spent making physical objects. Together with NSFT service users, we mapped graphic networks of support woven out of colour-coded crochet yarn. On huge sheets of newsprint with service providers we sketched out storyboards that told heart-warming stories of access to newly imagined services. With service users we erected table-top sets and shot painstaking stop-motion animations that brought to life the experience of coping with a mental health condition and gaining access to the kind of services young people want.

Of course it would’ve been easy to march in as the experts and conjure up all this stuff for them under their verbal dictation. But we knew that if we managed to work with them responsively and equitably as co-actors in a process of co-design, we would be more likely to unlock the personal capacities and knowledge resources latent in them, they would be the authors of what we co-produced, and there would be greater chance of buy-in of the findings that the workshops would give rise to. Ultimately, we would have a better chance of achieving an outcome that sticks and is sustainable.

Materials by their very nature offer resistance – physical resistance obviously but also syntactical resistance. It was really tricky to activate an intended signification through weaving yarn into canvas. It took a special kind of concentrated effort to convey the desired emotion through the movement of a figure in the animations. It took careful consideration to make sure the nuances of service provider stories survived translation into a series of dramatic sketched vignettes. One couldn’t be blamed for thinking that in this context of mental health services wouldn’t it have been a whole lot more straightforward and precise to simply write down everything everyone said? Without doubt it would, but that would be underestimating what the service users and service providers got from what was a different kind of reflection, a different sort of feedback from the physical objects and time-based visual media that they produced. The buzz in these making-workshops and the positive vibe that has continued in their wake proves there is something magical about them. This ‘magic’ has a social and communicative value that we need to spend more time articulating.

In his book The Craftsman, Richard Sennett sets to interrogating the value of making: “Display translates into a craft command frequently given young writers: ‘Show, don’t tell!’ In developing a novel this means avoiding such declarations as ‘She was depressed’, writing instead something like ‘She moved slowly to the coffee pot, the cup heavy in her hand.’ Now we are shown what depression is. The physical display conveys more than the label.” Sennett also says “We need to visualise what is difficult in order to address it. This is probably the greatest challenge facing any good craftsman: to see in the mind’s eye where the difficulties lie.”

We used making as part of a structured process through which NSFT could escape a paralysis that had descended on them out of well-meaning but ‘endless’ verbal discussion. We gave them licence to dream about better services – not of a developed youth mental health service but a completely transformed one. Today, with NSFT services users and providers, Early Lab is presenting this collaboration at the 3rd International Youth Mental Health Conference in Montreal.

Something made, whether it be a chair, a road sign, an animation or merely a rudimentary diagram or hurried sketch, has the potential to make things tangible – viscerally tangible in a way thoughts recorded verbally or literally don’t. And once tangible, real, and once real, action that before seemed beyond reach, can suddenly appear imminently possible.

Written for UAL Voices (University of the Arts London) when Nick Bell was UAL Chair Professor of Communication Design, 9 October 2015.